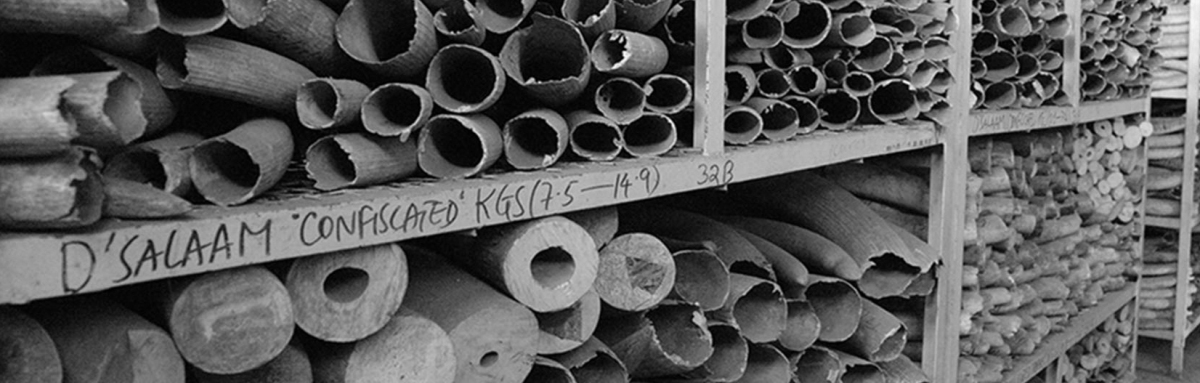

When customs departments find smuggled ivory they add the seized goods to a storage facility that holds all of the country’s reserves of ivory, called an ivory stockpile. These stockpiles are property of the government, and it is their responsibility to store and secure the goods from theft. In countries where elephants live, stockpiles are comprised of illegally poached ivory along with ivory accumulated from elephants that died of natural causes.

In 1989 Kenya burned its stockpile of ivory in an attempt to gain international awareness of the declining numbers of elephants. Soon after there was a dramatic shift in consumer demand for ivory and a global ban on ivory was imposed. The recent decline in elephant populations has led other countries to burn their stockpiles of ivory, hoping to raise awareness to the issue and devalue the tusks. Since 2013, the United States, Tanzania, Belgium, France, Chad, the Philippines, China and Hong Kong have all agreed to destroy their stockpiles of ivory.

Burning ivory was once the traditional method of destruction, but recently more countries are choosing to crush their ivory to ensure total destruction and to avoid fire hazards and air quality concerns associated with burning. Once burned or crushed, the piles of ivory dust, which are still owned by the government, are often put on display for educational purposes in museums, zoos or national parks.

Many countries that have decided to destroy their stockpiles make exceptions for certain pieces of ivory. For example, a country may choose to exempt ivory from destruction if it is classified as an antique, if it is used for conservation education or for research purposes. Ivory may also be exempt from a stockpile if it is used as evidence in a criminal case.

Some argue that destroying ivory will only increase its value, making the lucrative luxury good even scarcer. They claim that a controlled market with strict regulations might be a solution to generate income in many African nations, and that this money could even fund conservation initiatives. Four South African nations appealed the CITES ivory trade ban for this reason. Their large stockpiles of ivory were accumulating and the countries argued that the income generated from the sales of ivory would be used for conservation. Whether or not this method can work is hard to tell, but it would be a challenge to change the international conservation systems so that every country could benefit from a controlled market.